This feature was originally published in 2016 to mark the 10th anniversary of Peter Brock's passing.

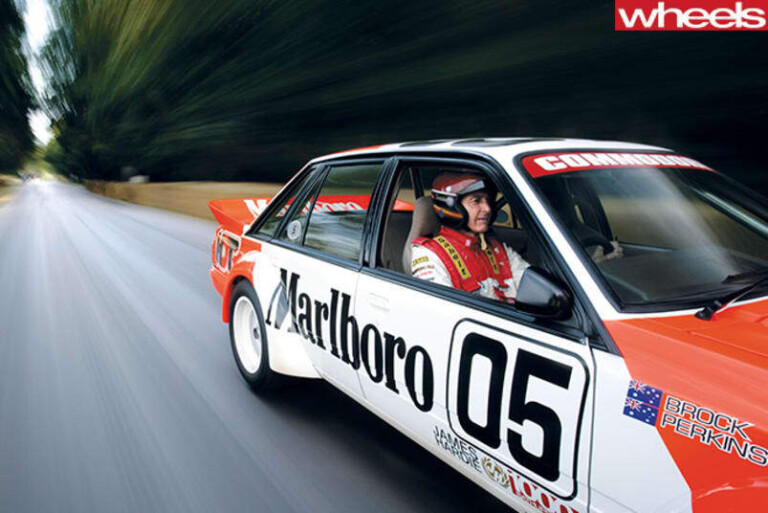

There are plenty of ghosts here in Hurstbridge, the heart of Peter Brock country. It was in this outer suburb of Melbourne that he lived much of his life, terrorising these roads in everything from bush jalopies to Holden factory prototypes.

There’s also a ghost at Bridge’s Restaurant, where a select group of friends, family and former colleagues have gathered for lunch on the 10th anniversary of Peter’s death. The last time we were all here was for Brocky’s wake. The room is full of poignancy.

We’ve come together again to remember Brocky with a perspective only the passing of time can provide. He was a hero to many, but he was also a friend, a partner, a boss, a colleague, a mentor... a mate.

Bev Brock knew her partner of 28 years better than anyone. She’s a strong and independent woman, yet remains defined by her surname, adopted by deed poll because she and Peter never married.

An unrelenting protector of ‘Brand Brock’, Bev is keen to dispel some of the less savoury myths surrounding her partner and, while everyone is respectful of her views, we all knew Peter pretty well and saw other sides of what she admits was a multiple personality.

Tim ‘Plastic’ Pemberton, Brock’s long-time publicist and a strong voice of reason in the face of some lunacy over the years, asks Bev: “Didn’t you once say you’d wake up in the morning and not know who was lying next to you in terms of which Brock he was that day?”

“It depended on his schedule,” she replies. “Where was he going? Was he going to a media schedule, a business meeting, into the workshop? And often he’d be dreaming it through the night, so he’d get up in character.”

One issue Bev is keen to address is the allegation of wife-bashing by Peter’s second wife Michelle Downes, a former Miss Australia and popular TV weather girl.

In my discussions with Peter, he questioned Michelle’s mental stability and said she was prone to hysterics that required him to exert physical restraint.

Plastic says Peter’s best mate Grant ‘Spear’ Steers, a brutally honest straight-talker who died last year, recalled witnessing Michelle losing control in an argument and falling down some concrete stairs, then reporting she’d been bashed.

Bev says he would literally not hurt a fly. “I know from the family stories it was a very dysfunctional relationship, but from the day I knew him, this was a guy who was so gentle. Not once did I see him lose his temper. Not once did he raise his hand to anyone. I had to release the mice down into the paddock, the kids weren’t allowed to have toy guns… I can never comment on him with [first wife] Heather or with Michelle, but certainly in the 30 years with me, he was far from that.”

At the end of our long lunch, though, Ian Tate, Peter’s first HDT mechanic, confides: “There’s no doubt it happened. I know of several instances, and I witnessed it once.”

Heather (who died in 2010) had said that Peter became aggressive when he drank, but Bev, while admitting he was “a lousy drinker”, never saw that.

Plastic remembers seeing Peter drunk “heaps of times”, and said he’d “go off” on occasion, but there was never any physical aggression. Just shouting.

“He’d just get very passionate about something because it was his nature to be passionate. Never was there a better drunk to run around with 05 on his car because that was about all he could drink!”

Brock’s fame took off in the early 1970s. “Peter was starting to get a big head,” says Tate. “He was married to a Miss Australia, and he was Mister Australia, and he was very difficult to get on with.”

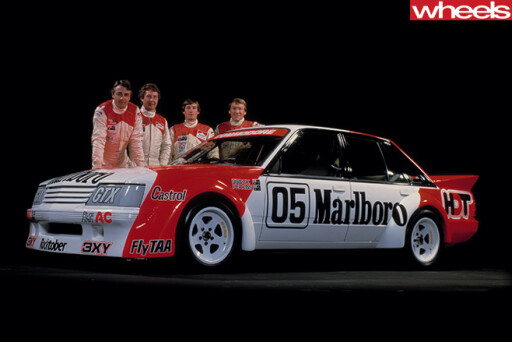

One outcome was that in 1974 Holden decided it could no longer tolerate him as the face of their ‘works’ team. Bad publicity dogged Peter’s personal life, he was experimenting with open-wheelers, demanding a prime city Holden dealership and rumour has it he was trying to pinch HDT’s Marlboro sponsorship. Holden decided to cut him loose for the first time.

“We cried when we heard; couldn’t believe it,” admits Tate, who encouraged Peter to seek opportunities with Vauxhall in Europe. Instead he chose to come back to Australia, and subsequently won the triple crown – Sandown 500, Bathurst 1000 and Phillip Island 500 – as a privateer in an L34 Torana, which simply enhanced his reputation.

Three years later in ’78 Brock returned to the Holden fold in a Torana A9X and dominated the sport like none before or since, winning Bathurst six times in seven years. There’s little doubt he had the best equipment in that era, but all agree he was the best driver out there.

“He was very special, no doubt about that,” says Tate. “The best three drivers in Australia were Moffat, Bond and Brock, and we were lucky to have two of them. Colin was quicker than Peter in the early days [but] it started to change over in 1971-72. All of a sudden Brock was doing it easy and Bondy was tearing the car apart trying to keep up with him.

“Leo and Pete Geoghegan were special in their day, especially at Bathurst. Leo was driving with Bondy [in 1973] and did a brilliant lap in practice and made the mistake of saying, ‘Nobody is ever going to go around Bathurst in an XU-1 quicker than that’. Peter said to me, ‘How much fuel is in the car? Enough to do three laps?’ I said yeah, and as he hopped over the counter he spat in the gloves, you know. I think he carved two and a half seconds off Leo’s time. Leo was demoralised. Peter didn’t say a word, just came back and said, ‘Okay, Tatey, put it away’.”

Plastic recalls asking a couple of Brock’s high-profile contemporaries if Peter was the best driver. “They didn’t like that question at all because it didn’t make them look too good.

“They said he was an excellent front-runner – get out front and he’d be away, turning immaculate lap after immaculate lap in the very best cars – not so good racing down in the pack because he wasn’t aggressive enough.”

Tate counters that, saying some of Brock’s best races were from the back. “There was ’73 at Bathurst when he ran out of fuel and lost a couple of laps and he caught back a lap on Moffat. That drive was bloody incredible. Lap times were the same for 30 laps through traffic, and don’t forget that in those days it was 60 cars on the track.”

Plastic reckons one of Peter’s best efforts was chasing the Jaguars in ’85.

“I reckon that was the best Bathurst driving performance. Those Jaguars were so far superior...”

“...and so illegal it wasn’t funny!” Tate finishes.

And let’s not forget Sandown ’76, when Peter and two mechanics built a Team Brock L34 in just two weeks, missed qualifying, ran-in the engine around the streets of Bundoora on Saturday night, started from the back of a 36-car field and still won the two-part ATCC sprint.

Jeff Grech, who worked for Brock in the mid-’80s, witnessed Peter’s heroic last lap at the ’79 Bathurst, when he broke the lap record for fun while leading by six laps in the HDT A9X.

“He came across the top on the brink,” Jeff recalls. “The car looked out of control but he was in control and that’s what’s always stuck in my head. And he would do that when we worked together, too. He would just get in the car, do two laps, and then waddle off.”

“The one that turned it for me,” says Bev, “was after Moff came and drove for us. We were at Pukekohe and Peter wanted to give Allan time in the car. He was grinding away lap after lap after lap, session after session. Then, with not much time left, Peter had to qualify. He does a sighter and then goes two seconds faster than Moffat managed. Moff was totally demoralised. He just turned to me and said, ‘We mere mortals just can’t do that’.”

But Tate defends Moffat as being a top operator in his day. “I still think Moffat was a very good driver. You can’t take anything away from him.”

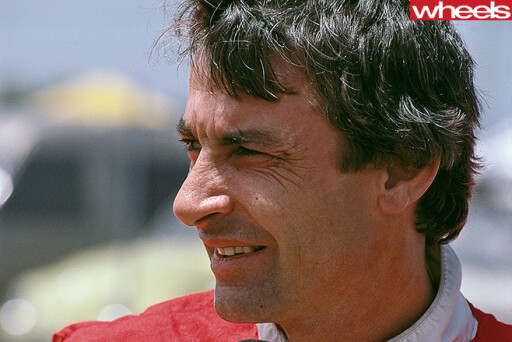

Craig Lowndes, looking younger than his 42 years, has come from Brisbane for this Wheels lunch. He is comfortable sharing his experiences with the old timers of a man he rates above all others.

“Brock was the greatest,” says Lowndes. “You have people who are naturally talented and people who have to work bloody hard to drive a car fast, and Peter was just naturally talented.

“I’d listen to the feedback he was giving Bridgestone, what the tyre was doing, what the car was doing; his feel and his feedback were exceptional. He could drive around issues when the car wasn’t perfect but his actual bum-seat-feel of what the car was doing was amazing.

“Every generation has its group of drivers, and cars change, but then you see the longevity he had in the sport and what he was still doing when I came along at the end ... even when he was retiring he was still top five so it’s not as if he was just hanging on to keep driving.

“When I joined HRT in 1994, I knew Sandown pretty well but when we went to Bathurst we had a mountain to climb. I was struggling, at least two seconds off the pace, until Peter sat me down in the back of the pits and talked through a lap, what you need to focus on, where you need to position the car, how to flow it across the grate across the top, and I still use those points today. I went from being frightened of the place to actually enjoying it.”

Come race day, the 20-year-old rookie found himself in the car at the finish and famously overtook John Bowe for the lead before having to settle for second with fuel running low. Brock’s protege has now won The Great Race six times.

In the mid-1980s Brock was at the height of his fame, making heaps, living fast and getting run-down. Bev recommended him to chiropractor Eric Dowker, who not only gave him an intensive 10-day ‘detox’ but introduced him to alternative thinking that included crystals. They soon invented the Energy Polarizer – named by Plastic without realising just how polarizing it would become.

Even today Bev provides a vigorous defence of the device, but her zeal has little effect on our other guests, who – after she leaves to collect the grandkids – openly condemn it as useless and the cause of the collapse of Peter’s empire.

Plastic believes Peter was deluded. “There are a lot of people around who’ll tell you what you want to hear. People just told Brock what he wanted to hear.

“I’ll tell you a little incident. About 12 months before this all happened, myself and Brock were sitting in the office and we thought up something or other. It was all bullshit but I thought it would be a good story to throw out to the media. Sure enough, it got a big run [because] anything [Peter] did got a good run.

“Then he said to me ‘That’s unbelievable because now it’s in the newspapers it’s true. It’s become a fact’.

“I said, ‘Come on, Peter, you’re starting to believe your own bullshit.’

“That was a frightening moment because it hadn’t happened before. You get to the stage where you’re surrounded by yes-people saying, ‘Yeah, yeah, that’s fine, go in your direction’, and it’s not what he needed.”

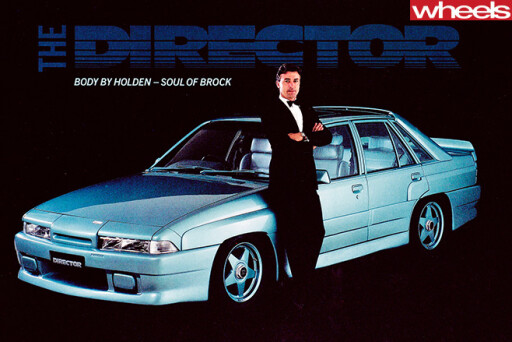

Grech, who in 1982 joined his hero as a young mechanic and saw HDT Special Vehicles grow into a powerhouse, regrets that the Polarizer and Peter’s refusal to acquiesce to Holden’s directive saw the business collapse.

“The sad part about the whole thing was just the upheaval of everything,” Grech says. “We were all sad about what could have been the Peter Brock empire. You just cringe. It was a licence to print money, even though he couldn’t run a business. Could you imagine a Peter Brock HDT with [former HSV boss John] Crennan running it? It would have been huge.”

The emotion of the day really gets to Bev when talk turns to the events surrounding Peter’s death. When Craig brings up the TV news choppers suddenly landing at his property, Bev recalls through tears how she hadn’t been able to contact Peter’s kids, James, Alexandra and Robert.

No one knows why he chose to race that Daytona Coupe in Targa West ’06, less than a week after being at the Goodwood Festival in the UK driving an old Humpy.

“Six weeks before, he rang to tell me that he had actually retired, and meant it; he’d lost his dreaming (because he’d always dreamed his events), he’d lost his timing, he’d lost the drive. He was really emotional.

“I don’t know why he changed his mind. He wasn’t even game to tell us [that he was doing the WA event]. We didn’t know. By his own acknowledgement, the car was a pig to drive and he couldn’t wait to fix it.

“When it came to retirement, I didn’t realise how deep his depression was. My last conversation with him was [tearing up again], ‘Bevo, I’m a failure. I’ve never done anything worthwhile. I’ve let you down, I’ve let the kids down, I’ve let myself down’.Peter was his own harshest critic.

“This was weeks before he died. I’m not saying the accident was a direct outcome of that, but he was questioning his own self-worth. For a man like that to come out and say those words…

“That was probably the most difficult time that you can imagine because it wasn’t the Peter we all knew. He was no longer the confident, self-assured, successful person. He was questioning every single thing he did.

“You try to focus on all the great things, but when someone you love dies, you want to think that they died content and happy with their lot in life. And you [just] know he was questioning.”

Later, Tate offers a counterpoint. He says Peter was incredibly happy that week in the UK, clearly in love with new partner Julie Bamford and positive about the future.

“I’d left him on the Monday to drive through the Cotswolds. The last thing I said to him was, ‘What are you rushing back for? Why don’t you spend a couple of weeks driving around with us?’ But he said he had to go. He had a commitment to drive the car and that’s all there was about it.”

As the waiters clear the main course, talk turns to Peter’s legacy. Each of our guests has a different perspective.

Plastic says Peter took motorsport into the general media. “Prior to that motorsport was on the car pages and that was it.

“He went way above that and became a notable person on anything. If you wanted a point of view on something that was going on, get Brock’s point of view, which would make a bit of sense … Peter just raised the whole profile, for which Craig is probably the equivalent now.

“One of the first things we did with Peter was when he won Bathurst and the race was worth $100,000, which at the time was huge. I thought here’s a bit of fun, so we went straight into the ANZ bank in Collins St with a photographer in tow and said, ‘Give us $100,000 so I can load this bloke up for a photograph and we’ll say it happened in your bank’. It got page 3 of The Sun or something, which you wouldn’t normally get in those days.”

Lowndes believes Peter’s legacy is the way he dealt with the fans rather than his on-track records.

“He’d stay signing autographs until the last person had come through. To have the patience to do that was incredible.

“Once, after I crashed at Bathurst, Peter said it didn’t matter what the result was on track, the fans are there to support you regardless, and for me that clicked pretty well. Even if you have a bad race you still get out and say hello to the fans, whereas a lot of the current drivers don’t seem to grasp that.

“And he wasn’t just a race driver, he was a mentor at the Olympics, and the whole thing with 05... Peter used motorsport as a vehicle to accomplish so many other things outside of the sport.

“If you look at Supercars right now, they’ve got a big problem. I’m probably the last of that old generation. I’m a qualified motor mechanic. Jamie [Whincup], for example, is not qualified at anything. We grew up in the same area and raced in the same go-kart club; his dad was a printer and Jamie says if he wasn’t a racing driver he’d be on the dole. He has no back-up outside of motor racing.

“Moffat and Brock is Jamie and I. Jamie won’t do a lot of the public stuff; he won’t put himself out there.

“It’s like [the current breed] have got this attitude it’s their right to be a race driver and they don’t want to give anything back. They’ll do the bare minimum that Supercars wants, like signing autographs. Peter was so good at that, but these guys, if they could dig a tunnel between the transporter and the garage to get away from people, they would.”

Bev says Peter never told Craig anything different to what he told the other young drivers, “but you’re the one that listened. That’s why you have the standing you do in the sport”.

“Peter never wanted to let anyone down,” Bev continues. “He would tell the other guys: ‘You need to remember that motor racing is only a small percentage of your life and if you want to have any relevance in the community you have to be more than a motor racer’.

“Peter was passionate about the environment, he loved his art, he loved breeding birds. He made sure there was a broader perspective to his life and he wanted others to do that.”

Grech compares Brock with the great global sports personalities. “I don’t say this lightly, but it’s probably a bit like Muhummad Ali was in America ... Peter was iconic. He related to a lot of people who didn’t watch motor racing. And he brought his love of the sport into the general public.”

“He was the total package,” Bev agrees. “There’s been a lot of very good drivers in Australia, but when it comes to dealing with the public and the media, part of the package was missing. Peter was bigger than the sport.”

Dessert is finished, our anniversary lunch is over. Time then to distil Peter Brock’s legacy.

One aspect of his multi-faceted and sometimes flawed character shines brightly: Peter was powered by his passion. It fuelled how he dealt with fans, how he drove, his road cars, the Polarizer, veganism, his environmental zeal… When Peter decided something was for him, he pursued it with a passion. Sometimes to his detriment, sure, but far more often the outcome was overwhelmingly positive. For Brock, for his fans, for motor racing, for the wider community. For Australia.

If passion was what he gave so freely, then it’s no surprise the fans were passionate in return. No other Australian race driver had as many diehard supporters. And no surprise that, of all the drivers who followed in his slipstream, his protege Craig Lowndes comes closest.

Ten years after Peter Brock’s death, his legacy is as simple – and as complex – as that. It’s how he lived, and how he should be remembered.

The crew

The Mechanic: Ian Tate

Mechanic 1969-1974 and Goodwood car preparer 2006

Harry Firth mechanic 1956-75; started car prep and engine-building business and continues to work there at 77; major player in historic car racing as long-time president of Victorian Historic Racing Register; occasional classic car racer

The Protege: Craig Lowndes

Teammate 1995-1997

Son of early-’70s Brock mechanic Frank Lowndes; six-time Bathurst winner; record 13 Bathurst podiums; first ATCC/V8SC driver to win 100 races; three-time series champion; awarded OAM in 2012 largely for work outside motorsport

The Manager: Jeff Grech

Mechanic 1982-1985 and team manager 1994-1997

Known to all as Hog because he used to ride a Harley; has worked for HDT, Perkins Engineering, Gibson Motorsport and Holden Racing Team; been involved in 10 Bathurst wins; now runs Team 18 with Lee Holdsworth in Supercars

The Partner: Bev Brock

Partner 1977-2005

Former science teacher; mother of three and grandmother of six; life coach; charity worker; yoga devotee; author of two books; awarded an OAM in January for her extensive community work; unsuccessfully trying to be retired

The Publicist: Tim ‘Plastic’ Pemberton

Publicist 1975-1987 and 1994-1997

Started Pemberton Publicity Services in 1976 to assist Peter Brock and the ‘05’ campaign for the Road Safety and Traffic Authority; contracted by Holden for three decades from the mid-1980s to promote racing activities; vintage-tram enthusiast

COMMENTS